“I remember applying for about 100 research projects in the United States and only being accepted for 3 or 4. I needed a lot of perseverance to continue on after that.”

The same perseverance that Fernando Mier-Hicks is talking about led him to fulfill his childhood dream of working at NASA on a robot with that name: the Perseverance rover.

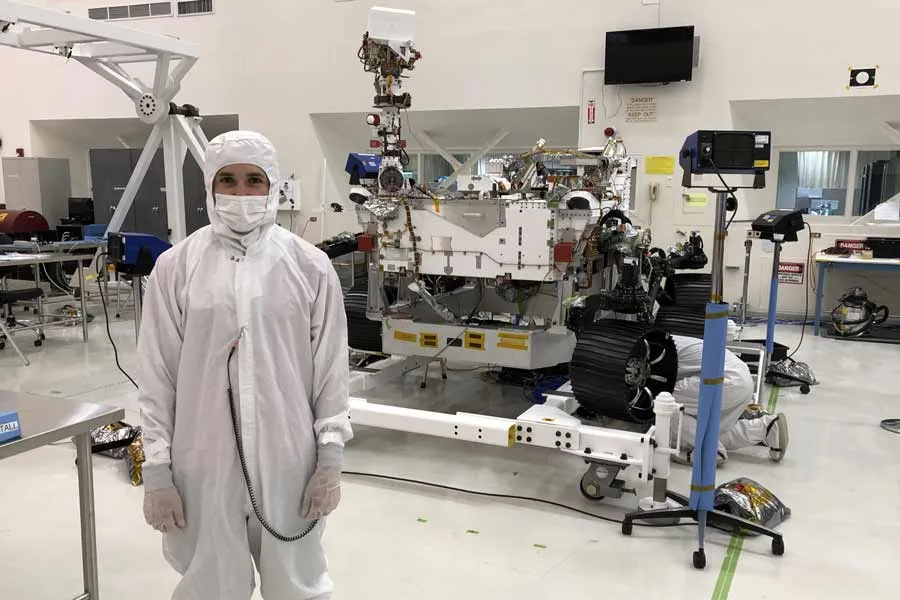

This Mexican helped in the creation of simulators and in testing the robotic arm on the rover, which successfully landed on Mars this past February 18th.

“I was very nervous. You’re betting years of work on everything going well. It was a relief once it landed. We’re very happy and excited to see what we discover on Mars.”

Fernando holds a degree in Mechatronic Engineering from Tec de Monterrey with a master’s and a doctorate in Aerospace Engineering from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

His work on the MARS 2020 mission

Fernando, 31, works at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in charge of the MARS 2020 mission, where he was assigned to help test the robot’s systems.

““(For example), the sample collection system is the most complex robotic system we’ve ever sent to another planet. It has 17 engines and sending 17 engines into space has many challenges,” he said in an interview with CONECTA.

For the robotic arm, he created an electrical simulator that sent the appropriate signals for correct movement.

“In this way, we were able to test the arm and check that it could be moved at the appropriate speed to connect it to the rover’s computer.”

Fernando had to work around the clock to learn the robot’s systems and work with different specialists.

“There were 100 people working on the robotic arm alone, and you have to coordinate with other areas to make everything work,” he said.

Fernando’s perseverance

The native of Aguascalientes knew that to fulfill his dream, he had to go to graduate school at a prestigious university in the United States.

To achieve this, he built up his résumé through research stays while studying at Tec de Monterrey.

“I knew I needed those stays to be accepted to universities in the United States. It was something I had to do. It was my responsibility and my own motivation.

“The Tec allowed me to get to where I am. Many of these stays wouldn’t have been possible if I hadn’t gone to the Tec.”

After completing them and graduating, he was accepted to MIT for the master’s program in Aerospace Engineering, which he completed successfully.

To transition to a doctorate at the same university he had to pass an admission exam that has a success rate of 50% among MIT students.

That moment was critical in his life, he says, because if he didn’t pass it, he was going to return to Mexico.

“What I did was study 4 hours a day for 6 months, with a timer. That’s how I was able to pass it.”

The robot that will search for Martian life

Perseverance will collect samples from Martian soil to prepare them for return to Earth in 10 years’ time, in order to look for signs of microscopic or fossil life.

“Inside the robot there’s practically an entire canning factory that seals the samples tightly. Testing and designing this whole system was very complicated,” he said.

The robot took 10 years to design, and all the components were assembled at the same time 3 years before its launch.

“Everything starts to get built in different parts of the lab. At some point, they come together like a giant Lego set. Before this, we have to make sure that each piece works perfectly and communicates with the other parts of the robot,” he said.

He added that the mission takes with it a helicopter called Ingenuity, making this the first time a small drone will fly on Mars.

His “blastoffs” before NASA

Fernando remembers that as a child, he liked to take apart his toys, cars, and planes. He then began launching small rockets, so he thought about inventing chemicals to improve their propulsion.

“(At 15) a compound exploded in my hand, and I got a third-degree burn. I was in the hospital for a week. From then, on I gave up chemistry and focused more on robotics, which is safer.”

When he started college, his future became clear: to find a way to get into NASA, he recalled.

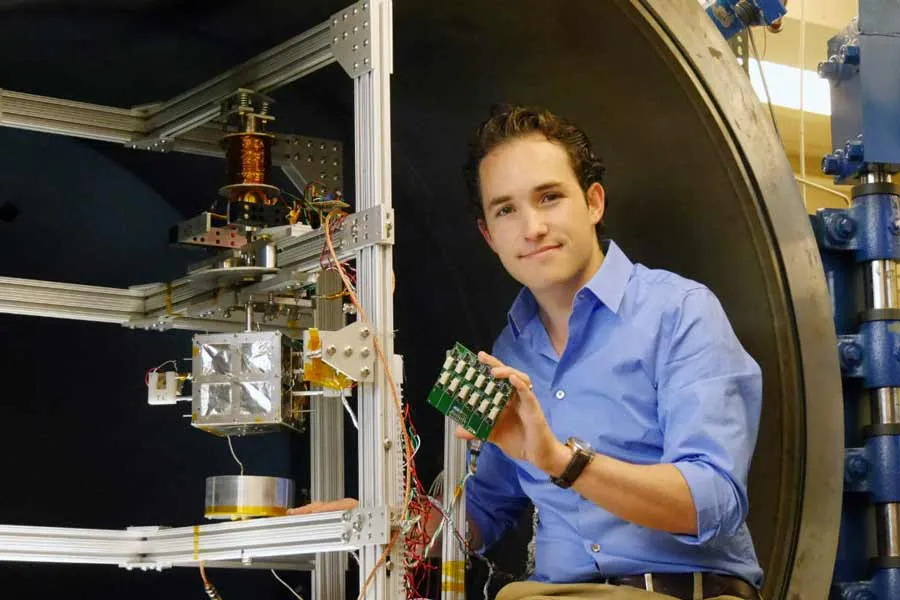

For example, he entered the space propulsion laboratory at MIT, run by the Mexican Pablo Lozano, to work on the development of electric thrusters for nanosatellites.

Along with others, he even founded the Action Systems startup to market these thrusters.

“(This startup) is still going, with 50 employees. For personal reasons, I decided not to work on it, and that’s why I joined NASA.”

For this work, Fernando was recognized by the MIT Technology Review in Spanish as one of the winners of the 2016 Innovators under the age of 35 in Mexico.

“I was very nervous. You’re betting years of work on everything going well. It was a relief once it landed. We’re very happy and excited to see what we discover on Mars.”

Space missions, the source of everyday technologies

Fernando said that great technological advances in today’s society are the result of space exploration.

“The technology that was developed to send people to the Moon is the reason we have Uber, Google Maps, and GPS on our cell phones.

“It’s hard to say now what the technology from Perseverance will give us in 50 years’ time. Perhaps humans will have already landed on Mars, which would be impossible without having had rovers on Mars, without knowing what the planet’s made of, without having studied it.”

He clarified that humans stepping on the surface of Mars is more complicated than going to the Moon,

“There has to be a political spark for NASA to invest the necessary resources, or if not, a commercial company like SpaceX will arrive there sooner.”

“The technology that was developed to send people to the Moon is the reason we have Uber, Google Maps, and GPS on our cell phones.”

The ancestors of Perseverance

Fernando mentioned that the first missions on the surface of Mars were Viking 1 and 2 in the ‘70s, which were “lander” robots that didn’t move.

In the ‘90s, NASA launched the first mobile rover: the Mars Pathfinder, which was the size of a microwave oven.

“It was the first experiment to determine whether rovers could be sent to Mars. After that experience, NASA then sent the twin robots Spirit and Opportunity,” Fernando said.

In 2012, NASA sent the Curiosity rover, the size of a small one-ton car.

“Perseverance is a twin to Curiosity, about the same size and weight, but whose difference is its mission: to collect Martian samples and prepare them for return and subsequent study on Earth.

“The previous strategy was to study Mars on Mars. Now we’re bringing Mars to Earth with the best instruments we have on the planet,” Fernando stressed.

His future plans

Fernando mentioned that he’s now being trained to drive Curiosity, which is still active, and then to drive Perseverance,

“Like learning to drive in Mexico, I’m being trained to drive the “old car” before driving the latest model.”

He also noted that NASA has to prepare at least two more missions to Mars to collect the samples from Perseverance. He estimates that this will take 10 to 15 years.

“Further in the future, we’ll be exploring the frozen moons of Jupiter and Saturn, entirely new, very interesting worlds. We’re very excited that one day we’ll be able to send missions to those bodies in the solar system.”

If you want to work at NASA, start now

Fernando’s advice is that when it comes to competitive issues, such as getting into U.S. universities or NASA, the earlier you start building up your résumé, the better.

“If someone wants to work at NASA, they need to have a PhD in an area relevant to NASA. To be accepted onto that doctorate program, you need to have done a lot of things at college.

“If you’re in high school or at university, it’s time to think, decide, and start working toward your goal.

“If you decide you want to work at NASA at the end of your degree, it might be too late, because you didn’t do what you should’ve been doing during your studies. The earlier you start, the better.”

The Perseverance rover took off for Mars on July 30, 2020. After traveling 471 million kilometers, it landed in Jezero Crater on February 18, 2021 for an estimated mission length of one Martian year (687 Earth days).

With information from Jorge Pintor.

YOU’LL DEFINITELY WANT TO READ THIS TOO: