Carlos and Germán used to go to the gym together and talk about basketball without knowing that years later both would be involved in the creation of an artificial lung-on-a-chip that looks to revolutionize medical treatments.

Germán García and Carlos Ezio Garcíamendez graduated in mechatronics engineering from Tec de Monterrey, where researchers Mario Álvarez and Grissel Trujillo were their advisors both in their studies and in a stay at Harvard to work on a “lung-on-a-chip”.

Together with other researchers from around the world, Germán and Carlos used their knowledge to replicate the function of pulmonary alveoli in a millimeter-scale device with the ability to do medical tests in less time and without experimenting on humans and animals.

Dr. Yu Shrike Zhang, head of the Harvard lab, says that this is a unique project in the world, being a three-dimensional chip, unlike other similar 2D models.

Cancer and COVID-19 are just two diseases that this chip can help generate new treatments for. This is only the beginning of the organ simulation projects Germán and Carlos hope to develop in the future.

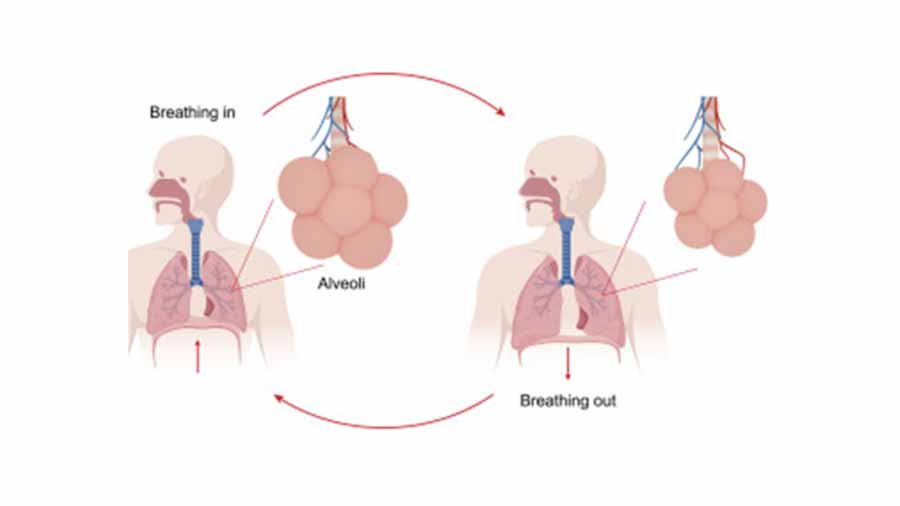

How a human organ is replicated

According to the National Cancer Institute in the United States, alveoli are tiny pockets that allow the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the lungs.

The project Carlos and Germán collaborated on consisted of developing a chip that simulates pulmonary alveoli in a three-dimensional model using hydrogel and human cells.

This model contains an expansion and contraction system that allows research in a simulated breathing environment, useful for simulating the effects of smoking, for example.

“The goal is to develop drugs for which clinical trials are limited or when there isn’t time to do clinical trials (such as in the COVID-19 pandemic).

“This lets us test different drugs and see how many work without the need for clinical trials on people and animals and the ethical aspects that that entails,” says Germán.

The project, led by Dr. Yu Shrike Zhang, involved researchers from different parts of the world such as Italy, the United States, and Mexico, including Carlos and Germán.

“We’re both mechatronics engineers and our role in the project was to develop the chip and be able to create the environment that you would find in an organ, to control the flow, the drugs, the cells, and the pumping, as well as control the humidity and temperature”, says Carlos.

The microchip measures 5 millimeters wide and 2.5 millimeters high and is mounted on a 1-cm-square mold.

It was developed at Brigham and Women’s Hospital at Harvard University’s School of Medicine.

In a statement from the medical center, bioengineering PhD Zhang says that this model is unique in the world.

“This is a first-of-its-kind in vitro model that can be used to test biological mechanisms and therapeutic agents, including anti-viral drugs for COVID-19 research,” Zhang said in the statement published on eurekalert.org.

Difficulties in replicating a lung

Working on the development of a project at Harvard that’s unique in the world while a pandemic was occurring was one of the most complex challenges Carlos and Germán faced.

“During the pandemic, many people returned (to their countries of origin). We still had the same workload, but there were fewer people,” says Carlos.

Having to do other people’s work for months was one of the most stressful moments of their lives, as their workdays extended to 12 to 15 hours on average.

“It’s so much pressure and stress. Everyone expects results, and there’s nothing else to do but the work,” says Carlos, who adds that Germán was one of his greatest supporters.

“He (Germán) told me to think long-term, to think about what was ahead: to raise the bar for our country, my family, and the Tec. Fortunately, he and I have supported each other,” Carlos recalls.

Today, both are on the list of the 19 authors of the article “Reversed-engineered human alveolar lung-on-a-chip model”, published on different scientific platforms such as pubmed.gov.

Difficulties in replicating a lung

Working on the development of a project at Harvard that’s unique in the world while a pandemic was occurring was one of the most complex challenges Carlos and Germán faced.

“During the pandemic, many people returned (to their countries of origin). We still had the same workload, but there were fewer people,” says Carlos.

Having to do other people’s work for months was one of the most stressful moments of their lives, as their workdays extended to 12 to 15 hours on average.

“It’s so much pressure and stress. Everyone expects results, and there’s nothing else to do but the work,” says Carlos, who adds that Germán was one of his greatest supporters.

“He (Germán) told me to think long-term, to think about what was ahead: to raise the bar for our country, my family, and the Tec. Fortunately, he and I have supported each other,” Carlos recalls.

Today, both are on the list of the 19 authors of the article “Reversed-engineered human alveolar lung-on-a-chip model”, published on different scientific platforms such as pubmed.gov.

“You have to get past the word ‘difficult’ to achieve what you want.” - Germán García.

Both scientists have promoted research stays at Harvard for Tec students, and Grissel has even received an international award for her work in organ printing.

“We started in Mario and Grissel’s lab in 2018. We owe them for this opportunity. They’re great mentors and have shared a lot of their knowledge with us,” says Germán.

That would be Germán’s entry into the world of bioengineering, but not before turning to his friend and inviting him to join in.

“Germán invited me. He told me about the Harvard opportunity, and I said, ‘If they can do it, I want to accomplish huge things like them too,’” Carlos says.

Their chats in the gym about a duo of Miami Heat players, Lebron James and Dwayne Wade, would end up with them forming a duo of their own at Harvard, where Carlos and Germán worked together on “the boards” of bioengineering and bioprinting.

Their future in organ simulation

When asked what word they would use to define the time when they worked on one of the organs most affected by the pandemic, they both mention “pride.”

“Family pride, pride for our country, for the Tec, for all the people who have supported us.

“It’s satisfying knowing the hours of work that we’ve contributed to this. That’s why we do it. Our goal is to change the world,” says Carlos.

With that idea, both engineers hope to continue collaborating on different projects for the simulation and creation of organs, such as the project for a simulated heart they plan to work on.

“In theory, it can be used to analyze different diseases in organs. If you have a heart that has irregular heartbeats, it’s possible to try to simulate that and recreate that environment without having to work on humans.

“You can see what kind of drugs or medicine can help cells heal,” Carlos says.

Germán also says that an article will soon be published about the work they continue to do in the area.

“It’s an area you can grow a lot in and achieve important things in the world.

“I’d like to continue on this path and god willing continue working on this type of project,” says Germán, who will also study for a graduate degree at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, in Switzerland.

“My advice to the next generations is to try. If you want to change the world, it’s possible, and it’s a great opportunity that you shouldn’t let pass you by.” - Carlos Ezio

For his part, Carlos continues to work in the Harvard lab full time and hopes to study for a graduate degree when he can.

They both collaborated on an article at Harvard in which they are the lead authors, which will be published in the coming months.

“My advice to the next generations is to try. If you want to change the world, it’s possible, and it’s a great opportunity that you shouldn’t let pass you by,” says Carlos.

“Don’t think it’s something from another world. It’s something that’s achieved through hard work and dedication.

“You have to get past the word ‘difficult’ to achieve what you want,” Germán concludes.

ALSO READ THIS NOTE: